365 Days of Unprecedented Need

The time before COVID-19 fully entered our collective consciousness feels so far away, so unrecognizable it isn’t fair to say they feel like 10 years ago – it is of a different place and time entirely.

It’s almost as if we all celebrated the New Year prematurely, ignoring a much more consequential marker of time: March 17, the day the Bay Area shelter-in-place order officially went into effect. The eve of which was not spent watching fireworks or drinking something bubbly, but panic shopping and hoarding toilet paper and hand sanitizer.

After a very long and very challenging year that has forever changed the fabric of our community, we do not celebrate but we acknowledge this occasion. Between March 2020 and March 2021 more than 529,300 (as of 3/15/21) people died of the coronavirus, tens of millions of people lost their jobs, hundreds of thousands of businesses shut down, and in the process, 45 million people nationwide – including 15 million children – were thrust into food insecurity.

“I was naïve.”

“I’m pretty sure I was at the office,” said Michael Braude, thinking back to when he first heard about the shelter-in-place order. “We already had been meeting to address our response efforts, but I don’t think anyone expected a complete shut-down to come from out of the blue as it did.”

Looking back none of us expected to be here a year later.

“I was naïve. I thought it would be over when the order was lifted – three weeks later,” remembers Gunilla Bergensten.

“A devastating blow.”

As the months wore on, we all saw the images of food bank lines nationwide and the heart-breaking portraits of those in them. For the Food Bank staff, this need was not distant. Day in and day out we saw our community hurting, we saw our neighbors, our friends, and our family in need.

“COVID has magnified the existing health and income disparities in the community I support,” said Lucia Ruiz. “This has been a devastating blow, which often causes me to feel both sadness and anger.”

Almost overnight we saw the need in our community double. In just 2 months we went from serving 32,000 households a week to 62,000 (we are now steadily seeing about 55,000 households weekly).

“Seeing the surge in people who needed food, oftentimes for the first time in their lives, kept me going,” said Joseph Hampton.

Keeping up with that level of demand was no small feat.

“The biggest challenge I think was getting food quickly while the retail market crashed. And operating at such a high UOS (Food Bank term for households) without increasing our physical working space,” said Angela Wirch. “With everyone panic shopping there was no getting rice…there were so many challenges. The money and infrastructure were gradual, but the need was immediate. We filled that second warehouse so fast.”

Two tractor-trailers, 10 bobtails, two new warehouses, and one giant tent to cover our parking lot later, we somehow found the space for 77 million pounds of food to meet the tremendous need.

Finding the People Power

“Never in my career have I experienced a more profound threat of not having a safe work environment for workers or enough workers available to run the operations,” said Nadia Chargualaf.

“Half of our team was incapacitated because of COVID, so we were short-staffed for a long period,” said Johnny Lee, remembering how many staff members needed to stay home because of their health. “Many of our sites were closed at the beginning, and a few remain closed to this day. We used some PPE before COVID, but now we follow all the guidelines given to us by the CDC and strictly try to enforce distancing between participants.”

Cody Jang remembers, “I was at work when the news came in. Within hours we had lost close to 3,000 volunteer reservations. We were worried about how we would complete the work without volunteers.”

But the community not only stepped up, they stepped up in droves. Within a matter of months, if not weeks, we were seeing twice as many volunteers as we welcomed pre-pandemic – that’ more than 157,000 volunteer hours since March 2020. Not to mention the support of Disaster Service Workers, corporate partners and community groups.

Challenges: Emotional and Physical

“The biggest challenge has been trying to stay safe during the days that I physically need to be at the office. Even after all this time, I still get a bit of anxiety when working in the office due to the extra layers of planning and endurance (mask-wearing, sanitation, etc.) that go into working within close proximity to others during the pandemic,” said Joseph Hampton.

“The biggest challenge is really the emotional toll that COVID is taking,” said Ken Levin. “Both in people we may know that have been directly affected, or those affected tangentially. This past Saturday, I brought food to a friend who had just lost a family member. I left it at her doorstep. Then on Monday, I attended an online memorial for another friend’s husband. Not being able to see, hug, and be with these people in their time of need has been particularly difficult.”

“There were multiple types of challenges to face. But one that I really wasn’t ready for was the isolation and loneliness of being separated from my loved ones,” reflects Lauren Cassell. “A lot of things in my life changed because of the pandemic, and I wish I had been more kind to myself. Having hard, unproductive days in the midst of a pandemic is okay.”

Policy Makers Rise to the Occasion

As the need rose, so did the public consciousness around food insecurity. Even before the pandemic 1 in 5 San Francisco and Marin residents was at risk of hunger. Food Banks can’t meet the need alone.

“Before COVID, getting movement from elected officials on policies that impacted low-income people was much more of an uphill battle. By thrusting millions more Americans into hardship, COVID forced politicians to listen to anti-poverty and anti-hunger advocates much more seriously and take immediate action,” reflects Meg Davidson. “Things we’d been told were impossible for years we were able to make happen in a matter of weeks. Turns out, we were onto something when we’ve been repeating that making it easier for people to get the help they need when they fall on hard times is good for everyone.”

“We adjusted, pivoted and made the necessary changes to help more in our community to reduce food insecurity during the pandemic. I’m proud of some of our legislative victories, such as, improvements to CalFresh, like waivers, increases in benefits, the P-EBT rollout, online EBT purchase ability, etc.,” said Marchon Tatmon.

Perseverance Despite the Weight of the World

“I feel very lucky to work at the Food Bank. As challenging as this year has been, I am grateful for my colleagues. I’m heartened by the generosity of our supporters,” said Iris Fluellen.

“There have been challenging moments, and breaking points, and everything in between, but we’ve kept the work going for our communities and for ourselves,” said Claudia Wallen. “My mom always says, ‘You must have a plan B, and if possible, a plan C.’ Never before has she been more right.”

“Being able to help so many new people get CalFresh benefits – and getting to know my staff’s pets – has kept me going,” shared Liliana Sandoval.

“Although I haven’t sat in my pod or met everyone internally or externally, I’m humbled to be a part of the team,” shared Denise Chen. “The dedication and commitment we have in serving our community is truly amazing.”

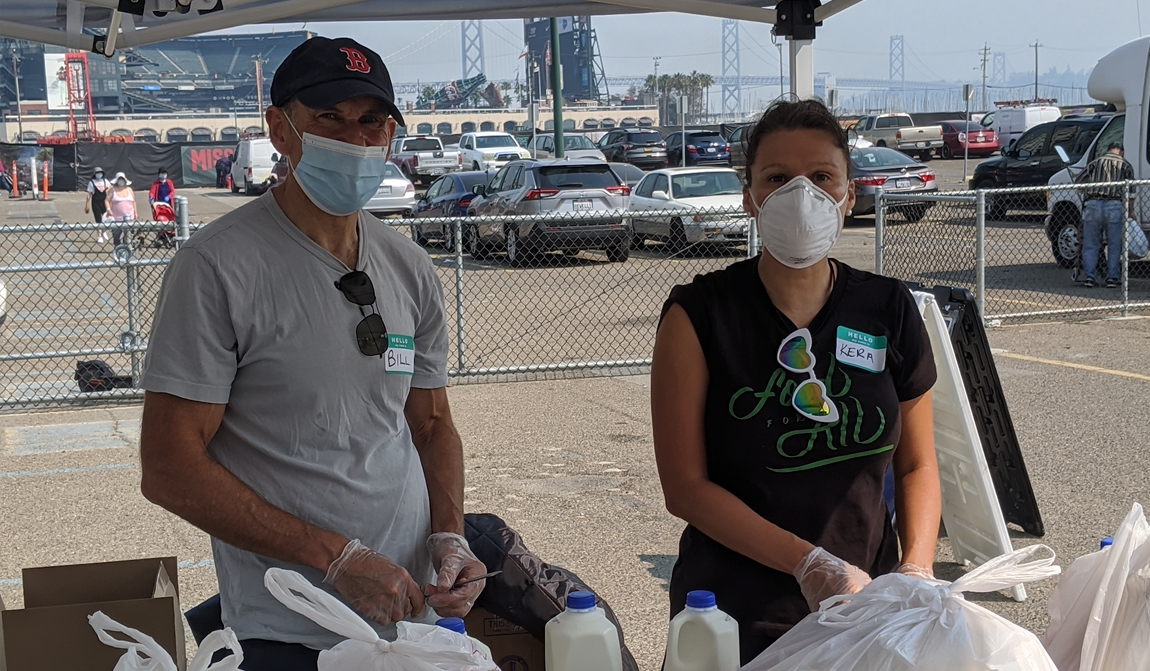

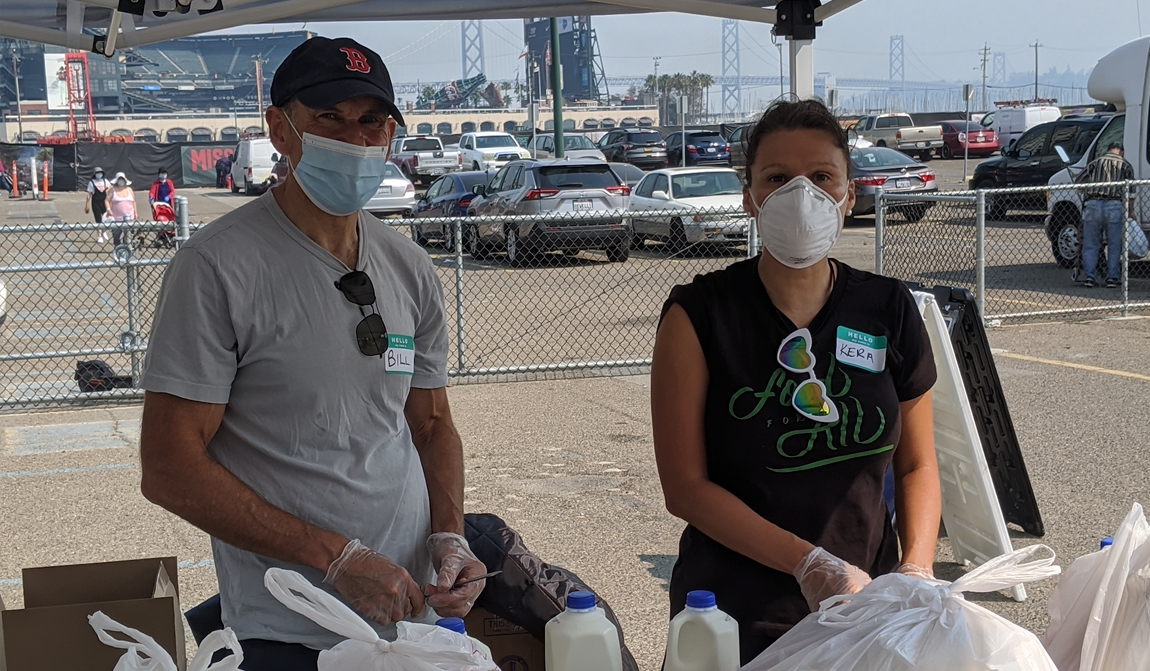

“Growth is messy, even when you plan it. We definitely haven’t felt like the most organized bunch on some days, but we did the work that needed to get done clear-eyed and together. My heart is so full of respect and love for each and every team member,” said Kera Jewett. “We may have been tired, sore, in PJs, short-staffed, and completely overwhelmed, but I know for a fact everyone did their level best every single day. I couldn’t ask for a better group of people to go into battle with.”

“Looking back I would tell myself, this looks really bad, but there are many, many good people doing amazing things to turn this situation and this world around, politically, scientifically, and morally, so keep your eye on the prize and don’t give up,” said Bob Brenneman.

More Stories

Follow us on Instagram for more stories from our essential team.

Follow Us

Fourteen years ago, Dru Devoe got on his Harley Davidson motorcycle and left his home in Florida with only clothes and whatever he could fit in his saddlebags. He landed in the Bay Area and eventually settled in Marin County.

Fourteen years ago, Dru Devoe got on his Harley Davidson motorcycle and left his home in Florida with only clothes and whatever he could fit in his saddlebags. He landed in the Bay Area and eventually settled in Marin County.

On a cold, damp San Francisco morning in late June, Clifford, William and Tommy sat together eating breakfast and sipping coffee in the parking lot of

On a cold, damp San Francisco morning in late June, Clifford, William and Tommy sat together eating breakfast and sipping coffee in the parking lot of  Food is central to creating community. When we can come together around a shared meal, we build connections, we foster understanding, and we grow together. And this isn’t true just of a family dinner or a special holiday celebration—meal programs like Glide’s are part of the fabric of our community.

Food is central to creating community. When we can come together around a shared meal, we build connections, we foster understanding, and we grow together. And this isn’t true just of a family dinner or a special holiday celebration—meal programs like Glide’s are part of the fabric of our community.

“People come to Glide where they receive breakfast, lunch and dinner, with much of the food coming from the Food Bank

“People come to Glide where they receive breakfast, lunch and dinner, with much of the food coming from the Food Bank Another COVID innovation is the Monday Pop-Up pantry on Ellis Street. Every Monday, the Food Bank and Glide work in close collaboration to thoroughly clean Ellis Street and set up a pantry where people can safely come and choose healthy food for themselves and their families. Since many in the neighborhood don’t have cooking facilities, the Food Bank provides foods that require little or no cooking.

Another COVID innovation is the Monday Pop-Up pantry on Ellis Street. Every Monday, the Food Bank and Glide work in close collaboration to thoroughly clean Ellis Street and set up a pantry where people can safely come and choose healthy food for themselves and their families. Since many in the neighborhood don’t have cooking facilities, the Food Bank provides foods that require little or no cooking. Covenant Presbyterian sits at the corner of 14th Avenue and Taraval Street and is deeply embedded in San Francisco’s Sunset District.

Covenant Presbyterian sits at the corner of 14th Avenue and Taraval Street and is deeply embedded in San Francisco’s Sunset District. By 10:15 – just as dancers are making their way upstairs – volunteers are downstairs cleaning up the food pantry. Week three after a more than year-long hiatus everyone is excited to be back.

By 10:15 – just as dancers are making their way upstairs – volunteers are downstairs cleaning up the food pantry. Week three after a more than year-long hiatus everyone is excited to be back. Just like the dance class, the pantry draws a loyal following of volunteers. Ranging in age from teenagers to over 90-year-olds, many have been coming since the pantry first opened its doors 15 years ago.

Just like the dance class, the pantry draws a loyal following of volunteers. Ranging in age from teenagers to over 90-year-olds, many have been coming since the pantry first opened its doors 15 years ago. What’s your overall pulse, 100 days in?

What’s your overall pulse, 100 days in?

For

For  In September the Food Bank approached several regular

In September the Food Bank approached several regular  For Patricia, the greatest reward was getting to know people. “Rather than just going up to a house and you don’t ever see them again, you see the same people every week. It’s a really nice way to develop a relationship,” she said.

For Patricia, the greatest reward was getting to know people. “Rather than just going up to a house and you don’t ever see them again, you see the same people every week. It’s a really nice way to develop a relationship,” she said.

When you

When you  Treasure Island didn’t even have a grocery store until

Treasure Island didn’t even have a grocery store until  Dave, a participant for over ten years, previously worked in landscaping and was barely getting by

Dave, a participant for over ten years, previously worked in landscaping and was barely getting by

Share